Once home, I started flipping through it, for hours on end, remembering the fascination its strange, tiny line illustrations held for my eight- or ten-year old self, on rainy afternoons when I'd been dropped off by my parents and when I could find nothing better to read in the house. (I should add that my parents owned a larger, more up-to-date, mid-seventies edition of the same book, one in which all of the line illustrations had been replaced by photographs and which consequently felt significantly less magical to me).

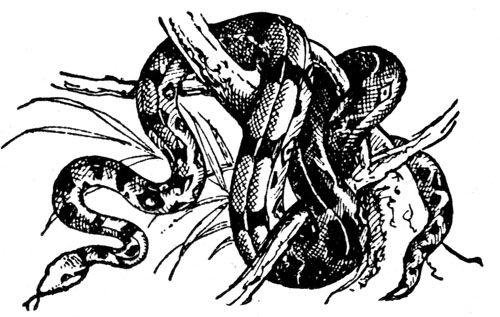

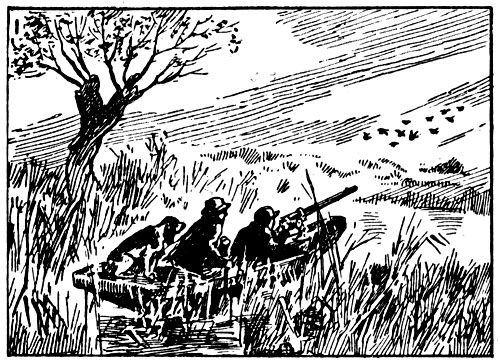

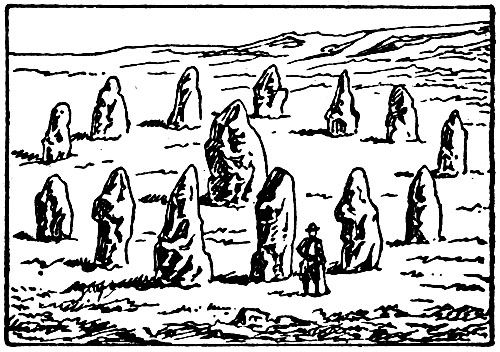

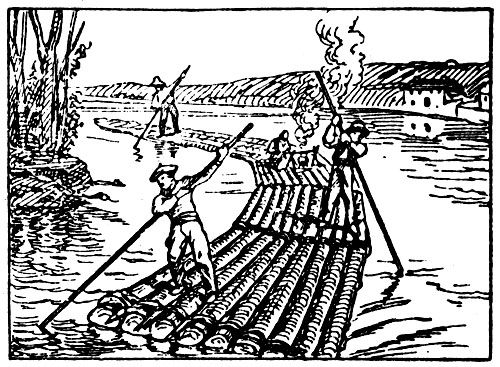

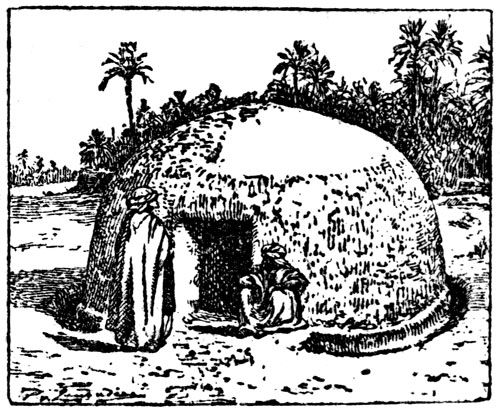

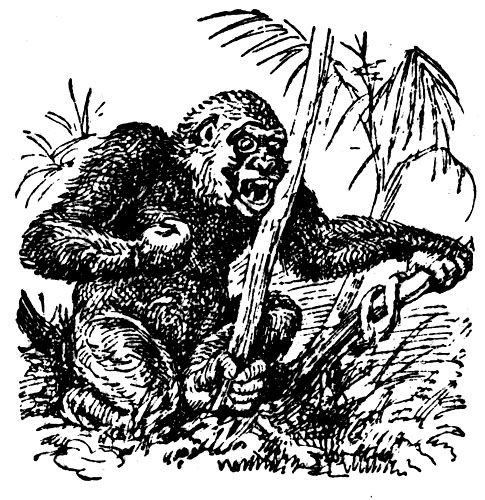

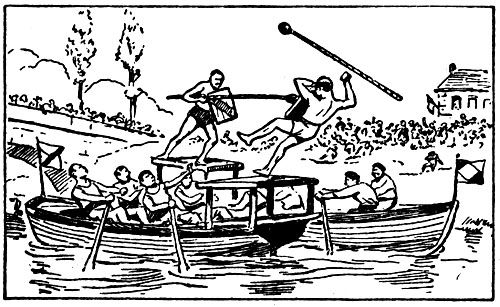

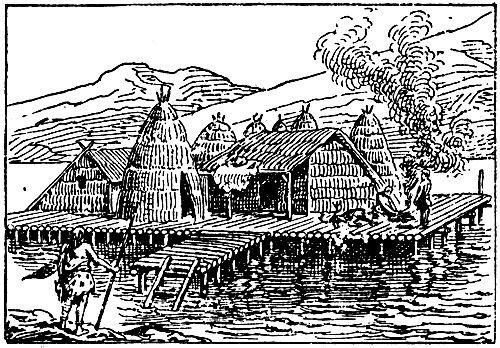

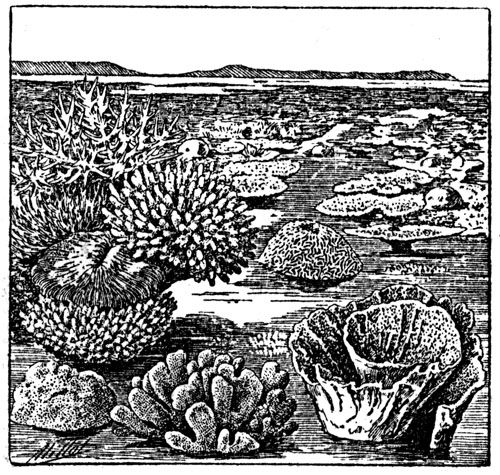

A dictionary, if you think about it, is a perfectly closed system, words referring to other words, definitions only made up of terms that need to be defined in their turn--until images are involved. The images function as an escape hatch from that seamless tissue of verbiage, and turn the dictionary into a machine for dreaming--dreaming of faraway places, long-dead creatures, obsolete modes of transportation, and natural phenomena one will never experience at first hand. I could go on about these illustrations forever--many of them seem to have survived from earlier, even much earlier, editions of the dictionary, maybe from the 1930's or even the 1890's, and some remind me of nothing so much as the book plates I had in my complete works of Jules Verne, another one of my childhood treasures--but I'd rather just show some of them to you. I've liberated them from their labels, the better to encourage reverie; and also because, the moment you don't know what they're supposed to be illustrating, each of them can open up a whole new world. Here then are my favorites, in alphabetical order, from B to M (and do keep in mind that, in the original, each one of these is less--some significantly less--than an inch high):

In their own way, they tell a kind of story, don't they?

Andrei, these are beautiful pictures; they have an emblematic feel, and there's something about their composition that even in the enlargements preserves an original sense of compression into a very small space. Whatever story they tell, it feels like a dream from some perverse lobe of the nineteenth-century brain (colonial-exploratory-exotic-mechanical).

ReplyDeleteActually, as I lined them up (in simple alphabetical order), they remind me of the illustrations commissioned by Raymond Roussel to his "Nouvelles Impressions d'Afrique," which seem to try to get at the same dream. (And I wouldn't be surprised if the illustrator he commissioned was also responsible for some of the Larousse images.)

ReplyDeleteThat makes sense.

ReplyDeleteReminds me somehow of the story about how when Joseph Cornell first showed "Rose Hobart" to the New York Surrealists in 1936, Salvador Dali rushed the projector & kicked it over, screaming that Cornell had stolen the idea from his unconscious.

ReplyDelete